IRSA - cheap Argentine property cockroach

Premium assets benefiting from Milei's reforms.

Summary

What it is: IRSA is an Argentine property company. Its main assets are a dominant mall portfolio and a premium development land bank. It is a cockroach that survived covid and some of the worst macroeconomic mismanagement on earth at the same time.

Why you should read this: IRSA is in pole position to benefit from Javier Milei’s reforms in Argentina. It trades at 1x an understated NAV that seems set to grow. It has a cash-generative and growing core business, a huge residential development project in the best possible location in Buenos Aires that will soon turn cashflow positive, an attractive land bank waiting to be developed, and an under-levered balance sheet. I believe it can reinvest internally and fund strong returns to shareholders for many years.

Potential returns: Bear case down 50%. Base case 15-20% for 5 years. Bull case 20-25% for 10 years.

Exchange: NYSE, ticker IRS.

Stock price and market cap: $18 per GDS (10 shares per GDS); market cap $1.4bn.

Year end: June 30th.

IR website: here.

Do I own it? Yes, at a 2% weighting, using moat and value mental models.

Disclaimer: This post is for informational and educational purposes only. Building Arks is not licensed or regulated to provide any financial advisory service and nothing published by Building Arks should be taken as a recommendation to buy or sell securities, relied upon as financial advice, or treated as individual investment advice designed to meet your personal financial needs. You are advised to discuss your personal investment needs and options with qualified financial advisers. Building Arks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but does not guarantee the accuracy of the information in this post. The opinions expressed in this post are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. The publisher may or may not hold positions in the securities discussed in this post and may purchase or sell such positions without notice.

Quick history

IRSA has been listed in Argentina for over 70 years and on the NYSE for over 30. It is controlled by Cresud, also dual-listed, which has a 53% stake. Cresud is in turn controlled by the Elsztain family. IRSA is the product of a series of acquisitions, mergers, and internal development. None of these is particularly relevant to the investment case today. What is relevant is that I think the Elsztains have been strong value-oriented opportunistic capital allocators over time, and have both protected and created value despite operating in one of the world’s basket-case economies. Recent examples include the sale of half the office portfolio at strong cap rates in the 5-7% range, the acquisition of “turnaround” mall assets at higher cap rates, the repurchase of shares at discounted prices, and the payment of significant dividends. That said, as with any controlled investment, there is always a risk that the controlling party does something that is not in minority interests.

This article focuses on the mall portfolio and the development land bank. The other assets - mainly offices and hotels - are smaller and don’t move the needle.

Malls

Malls are a staple in much of Latin America. Despite the rapid growth of sophisticated ecommerce platforms like MercadoLibre, malls are thriving for a range of reasons:

They’re air-conditioned, comfortable, and safe, in countries where street shopping sometimes isn’t.

They never got overbuilt like they did in more developed markets.

For high-end foreign brands, they’re the natural gateway to new countries and cities.

They’ve done a good job of evolving their brands and experiences to meet modern needs.

IRSA dominates the Argentine mall industry. It has 9 malls with a 67% market share in the City of Buenos Aires, and 8 malls in other cities with another 1 in development. Income-producing gross leasable area (GLA) stands at 371,000 today and will grow to 458,000 over the next 2-3 years new and redeveloped assets come on-line. Occupancy at the stabilised assets is 98%. This business has two key economic attributes. First, as with most real estate, operating costs are low relative to rent, so once the asset has been built, cash margins are high. Second, 75-80% of revenues are rents, structured with an inflation-linked base rate and a % of sales above a threshold. The inflation protection is critically important in a high-inflation economy like Argentina’s. The % of sales provides exposure to the compounding of real GDP, which will be valuable if Milei’s reforms succeed. The final 20-25% of revenue comes from a variety of smaller income streams like key money, concessions, parking, and advertising, all of which I would expect to rise with nominal GDP over time.

The combination of high cash margins and inflation-linkage means that IRSA’s malls are cash generative under virtually all economic conditions. However, in the company accounts this cash flow is merged with a variety of lower margin and more volatile income streams: hotels, real estate development, property sales, and the change in fair value of investment properties, which can produce wild non-cash swings on the P&L. These income streams are all likely to be profitable over time, but to the casual observer they obscure the attractiveness of the malls business.

Land bank part 1: Ramblas del Plata

IRSA has a land bank to die for. The crown jewel is Ramblas del Plata (RdP), an enormous plot in prime Buenos Aires within easy reach of the central business district and sandwiched between the redeveloped historic dock area of Puerto Madero, an ecological reserve, and the waters of the Rio de la Plata (known to history as the last resting place of the Admiral Graf Spee, one of Hitler’s pocket battleships).

It took IRSA decades to secure development permits for RdP, but in 2023 they got the final green light for an 866,000 square metre development. This is big - depending on the final design, there will be 6-10,000 homes plus office and retail space.

IRSA is using a capital-light development model for RdP. Most of the land will be sold to developers for an up-front payment, a mortgage, and a percentage of eventual sales, which is around 25% initially and is expected to rise towards 30% as the project matures. The up-front payments fund basic infrastructure like roads and utilities, and the percentage of eventual sales is almost pure profit.

Of the 866,000 square metres permitted for building, 693,000 is saleable. This will be heavily weighted towards residential, and IRSA has guided to a sale price of $4-6,000 per square metre for residential, which is easily to verified on online property portals. The exact proportion of other uses hasn’t been set yet, but I am not sure it matters: premium office and retail fetch similar or possibly higher pricing.

If the average sale is at $5000 per square metre, and IRSA gets 27.5%, they’ll recognise $950m in share-of-sale revenues at gross margins approaching 100%. After tax and discounted, this is worth $350-400m today depending on the exact inputs used. That’s similar to the value IRSA assigns to RdP on its balance sheet, so the asset is not undervalued today, but I’m happy to earn the discount rate as it gets monetised. In addition, if Argentina’s economy goes into sustainable growth mode we could see development being accelerated and real estate prices rising in real terms, both of which increase the discounted value. IRSA may also make positive cashflow on the upfront payments.

The bottom line is that RdP is going to be a huge generator of cash for IRSA over the next 5, 10, and 15 years. As of the most recent quarter (1q26), plots permitted for 116,000 square metres of buildable area had been sold or swapped with developers and sales of completed properties to final buyers should start in 2028.

One potential risk is that Buenos Aires property prices are higher than peer cities in the region such as Santiago and Panama City. This is particularly true for premium property. The differences aren’t vast, and can probably be explained by local supply conditions - e.g. Buenos Aires has limited waterfront property close to the city centre and central business district. However, during the bad years of Argentine economy policy, capital controls made it difficult to get money out of the country, and investing in premium real estate was one of the few good ways for the wealthy to protect against inflation. It’s possible that as the economy normalises, rich Argentines diversify into other assets, and premium real estate prices moderate somewhat. This is worth watching, although I think it’s more likely that prices rise with economic growth and increased mortgage issuance (see below).

Land bank part 2: the rest

In addition to RdP, IRSA has an extensive collection of smaller assets that aren’t generating income yet. Data from the company website and IR deck suggest that by developing or renovating all of these, IRSA would add around 400,000 square metres of saleable or leasable space, not including the projects that will grow mall GLA to 458,000 square metres. I don’t attempt to value these assets precisely: there isn’t enough data and I can’t assess permitting risk, although some assets are already permitted; but collectively these assets provide significant optionality for a savvy management team to reinvest opportunistically if the economic conditions are right.

The 400,000 figure does not include two huge plots near Lujan which could support 3.5 million square metres of building, mostly residential and saleable. These assets have been held for years and don’t get discussed, so I am not sure how valuable they are. At 8am on a Tuesday morning Google Maps puts Lujan roughly a 1 hour and 15 minute drive from the upmarket/CBD areas of Buenos Aires, which is theoretically commutable, but my experience of Latin American cities is that traffic can be unpredictable and when it’s bad, it’s bad. Still, these assets would move the needle if they came to life.

Viva la Libertad, carajo!

Something has changed in Argentina. Argentina’s political history is complex, but the Peronists have been the dominant political party for most of the post-war period (and when they weren’t, it was generally because they were banned rather than unpopular). Peronism is a broad church, but it has leant heavily left economically, and Argentina has paid a high price in inflation, lack of investment, and rolling economic crises. A lasting change to free market policies would do wonders for Argentina’s people and asset values, so it is highly relevant that pro-market (non-Peronist) candidates have won 2 of the last 3 presidential elections.

Mauricio Macri won the 2015 election on a pro-market platform. Unfortunately pro-market reforms usually entail pain before gain. In a bid to lessen the pain, Macri opted for slow reforms. It didn’t work - the benefits didn’t arrive before the 2019 elections. If he’d reformed the economy more aggressively, Macri might have won again, but in the event he lost to a disastrous Peronist government that stoked inflation to over 200%.

Enter Javier Milei.

Milei became President in December 2023 and has transformed Argentina’s political scene in 2 short years. He is that rarest of things: a charismatic free-market economist. His administration has ripped off the band-aid, balancing the government budget in a few short months, bringing inflation down from >200% to 20-30%, and taking a chainsaw to Argentina’s endemic overregulation. In the first 6 months this was painful, but Argentina’s economy has since responded, accelerating to 4-5% growth. Poverty is down, Milei’s party recently won a significant victory in the midterm elections, and his approval rating is high. There are challenges ahead - not least accumulating sufficient fx reserves to float the currency - but Milei’s Argentina is going in the right direction.

A free market Argentina has immense potential. In the 1980s a team of economists trained under Milton Friedman in Chicago reformed Chile’s economy along strictly free market lines, and the result was a 30-year economic miracle, with rapid economic growth, a massive reduction in poverty levels, and net cash on the sovereign balance sheet. Argentina is not Chile, and 2 years is a long time in politics. But at the same time, I think Milei’s reforms are going to work. If they do, then going into the next election in late 2027 the economy will be growing, jobs will be being created, inflation will be down, and living standards will be rising. That’s a very good backdrop for re-election, and if Milei serves 8 years he might create a “new normal” in Argentine economic thinking. In Chile, the left won every election from 1988 to 2010, but they didn’t undo the Chicago reforms because they were working so well. (It was only when the next generation, who did not remember the bad old days, came to dominate politics that the reforms came under real threat - and even then, the changes have been fairly minor - the real damage has been to confidence.)

There is a chance Argentina is at the start of that journey. For its own sake, I hope it is.

The mortgage market

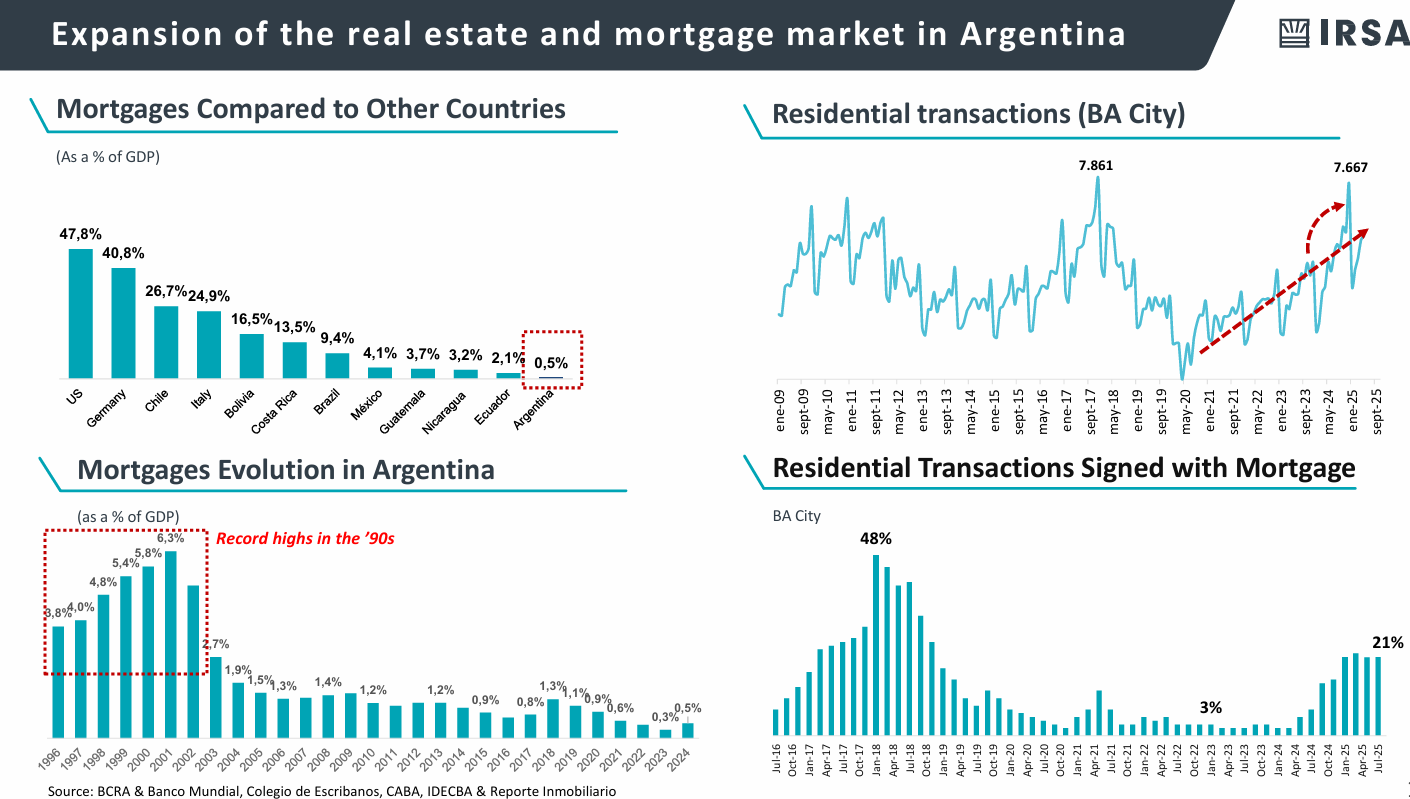

After years of low issuance and high inflation, Argentine private sector debt to GDP is around 8%. Within that, consumer debt is around 5% and mortgage debt is around 0.5%. This is incredibly low: in the US mortgage debt is worth 50% of GDP and in neighbouring Chile it is nearly 30%.

What banks need in order to lend with confidence is controlled inflation and stable interest rates. Banks have already started lending again in Argentina, and if conditions continue to stabilise lending will only accelerate. Sustained debt issuance over 5-10 years would likely have a significant impact on investment, job creation, consumer spending, and premium real estate prices. IRSA owns malls and premium residential development properties. It is hard to imagine a company better placed to benefit from a reflation of the Argentine economy.

Balance sheet

Side note: the Argentine peso is volatile against the dollar, so when converting balance sheet values to dollars you need to be careful to use the exchange rate on the balance sheet date. However you can think about IRSA in dollars: its assets are all either inflation-linked or dollar-denominated, and its debt is in dollars.

IRSA’s balance sheet is under-levered. As of September 2025, IRSA has $500m of debt and $190m of cash. Maturities are manageable, with the majority after 2032. Rental ebitda was $190m in 2025. This puts net debt at 1.6x historic ebitda, and rental ebitda will grow with real gdp and mall GLA growth. The loan/assets ratio was 9%, but I think assets are understated. Malls represent 43% of assets, and due to the lack of a liquid market for malls IRSA values its malls using a DCF. At year-end 2025 the discount rate was 11%, giving a valuation of 7.5x mall ebitda. In offices, where there is a liquid market, IRSA has been selling at cap rates of 5-7%. I suspect the lack of a liquid malls market is due to the scarcity of assets and IRSA’s dominance in the sector, and that if IRSA wanted to sell malls it could achieve cap rates well below 11%. In other words, I think IRSA carries its malls below market value and the loan/asset ratio is even lower than it looks.

Low leverage made sense in the highly unpredictable economic environment IRSA faced from 2019-2023, especially since IRSA did not have cash taxes to pay. It will not make sense if the economy continues to stabilise. Management have started increasing leverage, issuing a $300m 10-year dollar bond at 8% in the middle of 2025, and I expect this to continue slowly - potentially for many years as asset values rise. This means IRSA has 3 big sources of cash to fund landbank development and continued returns to shareholders: operating cashflow from the malls, development cashflow from (in particular) RdP, and rising leverage.

Two other balance sheet observations:

IRSA’s main liability is deferred tax, which is largely payable if they sell assets. However, much of their asset base is probably going to be held in perpetuity. If the deferred tax is never going to be paid, that value arguably accrues to IRSA’s shareholders, and book value could be thought of as being up to 40% higher.

IRSA owns a 29.9% stake in a government-controlled mortgage lender, Banco Hipotecario. This is separately listed and trades at 1.5x book value, putting IRSA’s stake at $150m. Banks in more stable emerging markets often trade at 3-4x book.

Valuation

IRSA trades at $18/GDS and a $1.4bn market cap. Using the most recent (1q26) balance sheet NAV of $1.3bn, that’s a multiple of 1.1x. As argued above, balance sheet NAV likely understates true value given the discount rate used in malls and the deduction of deferred tax payable on sale.

The bear case is that Milei loses the next election. Between 2020 and 2022 the stock traded in a range between $3 and $5. I don’t think it will go there again for 3 reasons. First, that period included covid. Second, by making freedom popular May have changed the political discourse in Argentina for a generation; if so, the only way for the Peronists to regain power will be to move to the centre. And third, when the stock hit its lows RdP wasn’t permitted, whereas by the next Presidential term it will be generating cash. If Milei loses I could see the stock halving, which puts me off making IRSA a large position, but IRSA is a cockroach: it’s survived Peronism before and would again. At that price it would be dirt cheap and I would likely slowly accumulate shares.

The base case is that Milei wins again, the economy grows for 5 years, mall cashflows rise, discount rates come down, RdP starts generating cash, development of the rest of the land bank accelerates, and leverage rises slowly. In this case NAV could double over 5 years, the premium to NAV could expand somewhat, and IRSA could pay significant dividends, for a 15-20% 5-year compounded total return.

The bull case requires that we are at the start of Argentina’s “Chile moment”. Real GDP grows at 4-5% for 10 years driven by rising corporate and foreign investment. This creates vast wealth and the middle class expands significantly. Mall ebitda compounds at 7-8%, inline with nominal dollar GDP. This combined with a reduced discount rate triples mall NAV, enabling IRSA to borrow an additional $1bn, pay a 10% dividend yield for 10 years out of debt proceeds and mall income, and grow its NAV by 50%. RdP produces $750m of after-tax cash flow, adding another $400m of NAV. IRSA leverages the $750m with another $750m of debt to build $1.5bn of leasable assets. The cap rate at cost is 8%, so this generates $120m in annuity ebitda. However the market rate for these properties is 6%, so the finished assets are worth $2bn, adding another $500m of NAV. With mortgage issuance booming Banco Hipotecario’s book value compounds at 15% in dollar terms and the stock trades at 3x book, adding another $1bn to NAV. In total, NAV triples over 10 years for a 12% CAGR, and Argentina’s stock market prices in a continuation of the good times so the valuation rises to 1.5x NAV. This gives a 15% 10-year stock price CAGR plus a 10% average dividend on the current share price. None of these are specific predictions, but I don’t think the assumptions are heroic either - rather, what produces exceptional returns is that IRSA could feasibly do all of these things at the same time.

Conclusion

The absolute downside is greater than I would like, especially given the difficulty of assigning a probability to the next election outcome. But overall this is the kind of investment I love: a solid and fairly high-probability base case, with a bear case I can live with and an exciting but not unrealistic bull case. I am happy to hold IRSA at the current price, and would likely add on a significant drop.

I love the write up, it looks like the bear case might be too pessimistic especially since it looks like Milei's reforms hold (as current trends suggest), IRSA looks poised for asymmetric upside.

What are IRSA competitors and how are they stacking up against them?