Mental models

There is a balance between flexibility and discipline.

Many investors pigeon-hole themselves into an investment niche or have hard-coded rules and checklists. In effect, they use one mental model. This makes selling a fund simpler, but reduces the opportunity set.

At the other extreme, investing without clear mental models allows you to make an excuse for buying anything. I think fitting each stock to a mental model helps me identify what really matters and make unemotional decisions as new facts emerge.

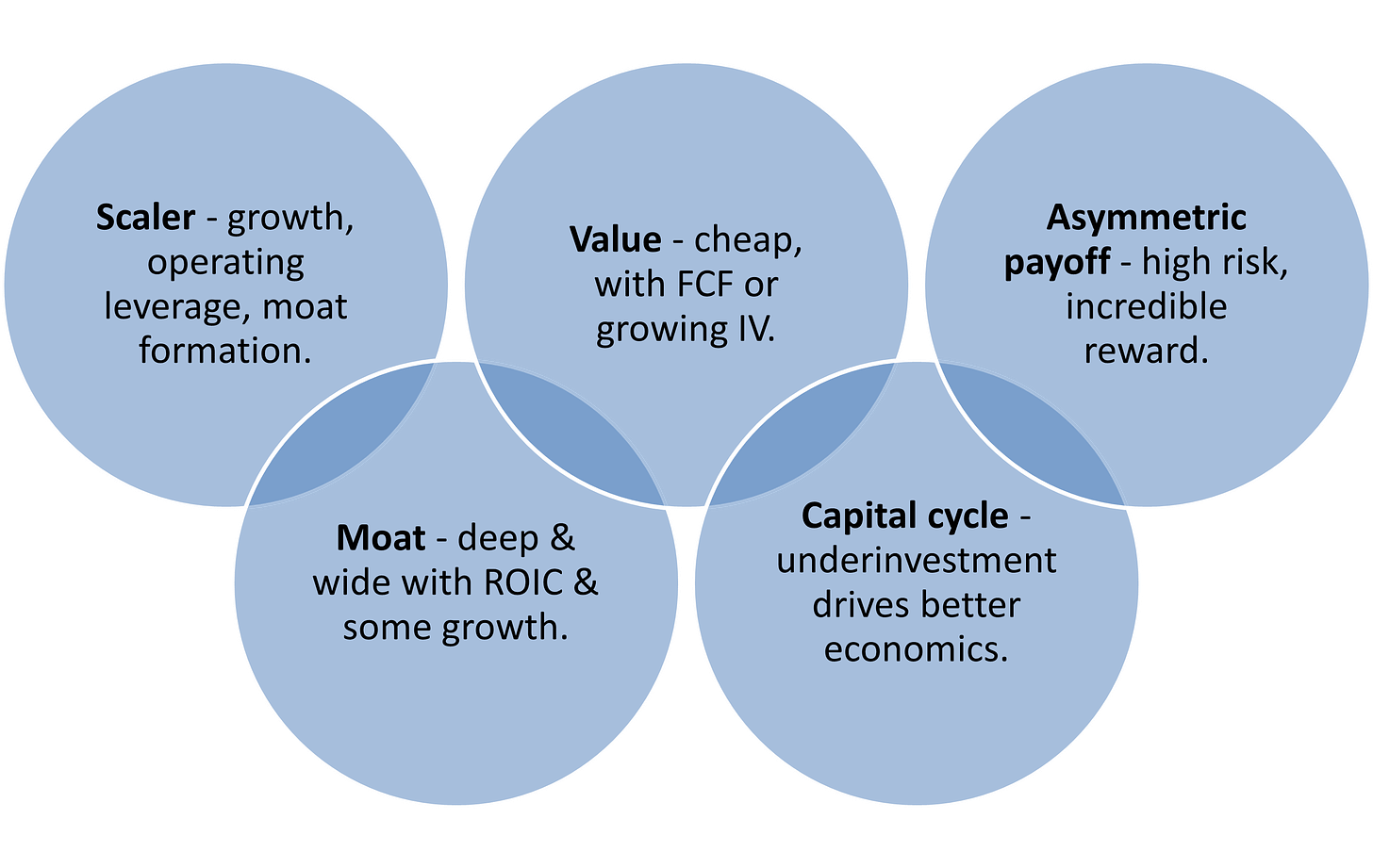

I use 5 mental models. Having more than one allows me to go where the opportunities are without losing discipline. My mental models often overlap:

Scalers are able to grow revenues rapidly over relatively fixed costs, driving operating leverage. They show promising signs of being able to form deep moats, but these moats are not yet fully formed.

Moat businesses are fairly mature and have deep economic moats allowing them to earn above-average returns on capital. They are usually able to combine moderate revenue growth with operating and financial leverage to compound earnings attractively over time. Management is key. Moats are not an intrinsic feature of a business, especially in younger/smaller businesses. Moats are the result of good management decisions compounded over time. They can be strengthened, and they can be weakened. Perhaps the deepest and least-appreciated moat is exceptional management and carefully-crafted culture, which can turn even a fairly commoditised business such as insurance into a moaty compounder like Berkshire Hathaway.

Value investments are available at a fraction of their intrinsic value. However, in my experience you need either growing intrinsic value or free cash flow and excellent capital allocation to make value investments work. Cleverer people than me might make money out of melting ice cubes or dirt cheap stocks with bad capital allocation, but it hasn’t worked for me.

Capital cycle investing relies on the idea that when an industry is making good profits, capital floods in, increasing supply - but when the profits collapse, capital exits, reducing supply. It is much easier to identify supply trends than it is to predict demand, which is what the market usually focuses on. Therefore, is often possible to buy equities in industries where demand is shrinking cheaply, before the improvement in economics that inevitably follows.

Asymmetric payoff is fairly self explanatory. Occasionally I find - and can’t resist buying - equities where the probability of success may not be very high, but the magnitude of potential success is enormous. I only ever buy small positions in these stocks for obvious reasons.

Disclaimer

This website is for informational and educational purposes only. Building Arks is not licensed or regulated to provide any financial advisory service and nothing published by Building Arks should be taken as a recommendation to buy or sell securities, relied upon as financial advice, or treated as individual investment advice designed to meet your personal financial needs. You are advised to discuss your personal investment needs and options with qualified financial advisers. Building Arks uses information sources believed to be reliable, but does not guarantee the accuracy of the information on this website. The opinions expressed on this website are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. The publisher may or may not hold positions in the securities discussed on this website and may purchase or sell such positions without notice.